|

The journey at its start had proven far more fruitful than either Manya could have anticipated, and that was plenty enough to bolster confidence—enough that the unknowable path that stretched before them had at least a guiding light to prevent them from wading through dark waters again. The two had stumbled upon a coastal town near where Kalua disembarked, a place where the clear skies they were familiar with seemed just a little closer, and the sight of it was spiriting.

Lodging at an inn (a far nicer one than Yona had found herself in along the way), Rory retrieved the doll from his poncho pocket and the pair looked at it thoughtfully, felt their paws over the handiwork that had once been admired from a distance, marveling at the craftsmanship of the thing that seemed nearly alien in its immaculate design. Then Yona reached for the key attached to its back, and instinctively began turning it, wondering if the assistant might come alive once more—if only to say hello.

To her astonishment instead, what might have been a phantom or a specter released from the last gasp of the doll’s breath, and, in the span of half a second, both thanked the pair and instructed them where to look next in a voice unlike any sound they had heard, before becoming one with the humid hotel air around them. The visitation left them feeling both chilled and oddly ticklish, as if they were giddy children passing notes in class once more. It was strange how instantly the spirit communicated the message, they thought; almost as strange as there being a spirit to begin with. Not much would be said again about the encounter.

* * *

In Yona’s travels that night in an unfamiliar bed, she found herself in some edition of Eltrya where the magic barrier was thriving and pulsating, so much that magic was coursing through her body as strongly as her blood, and she knew this must be the distant past. So could that mean—

“Ceris!” she cried, as the emerald-green mane of her friend bobbed over the sunkissed horizon. For a flash of a second she fretted that this was a battlefield, being a rather barren and open expanse as far as she could see, and there always had been the possibility that she could layer travel to a time as inopportune as this, given Ceris’s disposition. But luckily no horns were blaring; no squadrons were assembling. So why, then, was Ceris running toward her with such urgency?

She shouted, “Ceris! I haven’t seen you in years—in my time.”

“Hurry, fair child,” she cried, but not without her dignity still about her. “Up—up the ledge!”

Startled as she may be, Yona was still as eager for adventure at twenty-two as she was at eight, and perhaps a high-speed chase, whatever may have been pursuing them, was just what her little beastly heart had been desiring. Latching her claws into the gravelly cliffside, she nimbly scaled past flowering cacti and prickling bramble, all the while glancing anxiously behind her in the hopes she would see Ceris, and ideally not her pursuer, close at hand. After Yona had safely scrambled to the cliff’s edge she finally saw Ceris below, lunging her beloved blade Shalon into the very trail of claw markings Yona had left behind, skillfully scraping past obstacles to greet her friend, albeit with more fatigue behind her breath than Yona was accustomed to seeing. Whoever—or whatever—had been giving her chase was out of sight. Yona helped her up by the paw, though Ceris’s white gloves were tattered and ragged.

“Looks like whatever it was, you managed to escape it this time, eh?” Yona said merrily, as if no more than a day had passed between their interactions. “Ceris, I don’t think we’ve seen each other since I was, what, twelve? Thirteen? Don’t I look much taller now?”

The look of uneasiness that had stained an otherwise stoic, bright face such as Ceris’s had been more than a little disconcerting to Yona, and perhaps the elder Manya noticed this, as she hastily replaced it with a smile. “Yea, and thine head hast finally grown to fit thine hat.”

Yona chuckled, a little more nervously than she intended. “I really caught you at a bad time today, huh? You’re not hurt, are you? …What exactly were you running from?”

Ceris removed one of her yellow slippers to shake a rather jagged rock from out of it, hoisted her cape neatly behind her, and fitted her cap back onto her mane straight and proper, then said, “Little Yona, doest thou knoweth not to expend magic use beyond necessity?”

“What do you mean? My headmasters talk about that sometimes—Pamela especially—but why do you bring it up? Isn’t the magic barrier still good to go in this era?”

“Heavens, thine phrasing giveth me not much faith in the future. Nay, lass, the barrier is not the sole concern. A body can only taketh so much.” She removed the tattered gloves, shaking dust and dirt and blood from out of them, and looked Yona in the eye to say, “And mine hath been pushed to its limit by this raging war.”

A frown cast itself like a shadow over Yona. If one of the most trusted adults in her life still dealt with such limitations and uncertainties, how could she ever hope to grow old with confidence?

“Ah, but worry not. ’Tis because I am older, eighty-five years to my name, and still I draweth upon magic in battle as though I am a child at play. Nothing hath deterred a body so spry, unlike this one which withers before thine eyes. Dear one, tell me thou shalt not repeat my mistakes and rest, rest whenever thou can, or the fatiguing years shall be ahead of thee.”

Yona nodded warily and awoke with the morning sun.

* * *

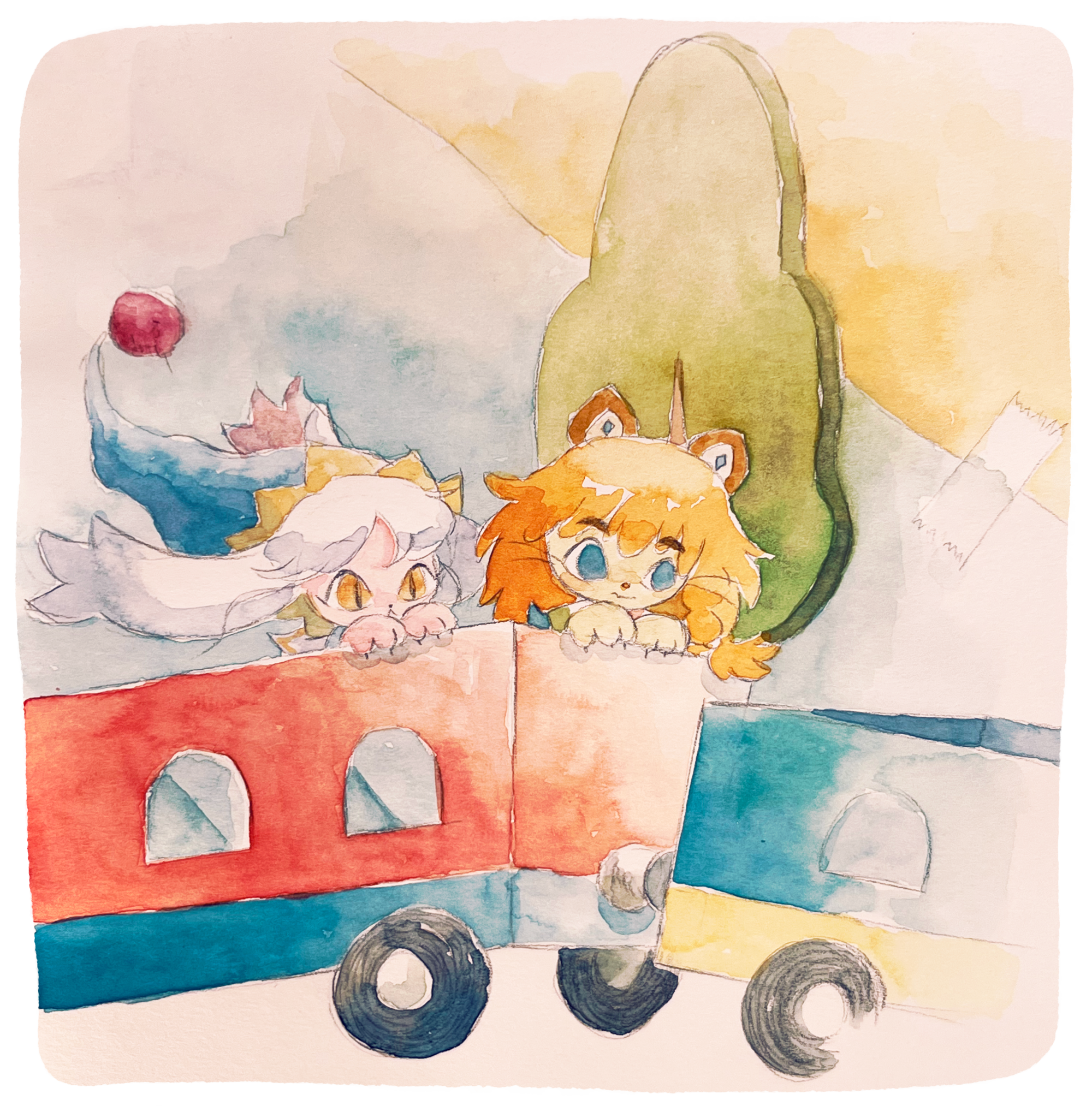

It was a quiet dawn in the still-overcast town of Mesmera Village, and the two sleepy-eyed travelers had packed their things and gathered their wits to check out of the hotel and prepare for the next leg of their journey, when suddenly like rolling thunder came the footsteps of a child from down the hall blazing past them, dropping rather a lot of toys along his way. Rory rubbed at his eyes then reached for a toy train, painted all in primaries, to say, “Hey kid, you dropped something…” but the child was already long gone.

“What’s all this stuff? Why was he carrying so much…and why didn’t he stop to realize he dropped it all?” Yona said, cautiously picking up a piece of a train track, surveying it as if it might contain some mystical cipher. “This is nice stuff, too—we didn’t get toys like this at Hearts and Diamonds.”

Rory sheepishly refrained from mentioning the one-of-a-kind, artisanal toys his parents had showered him with—in the absence of any meaningful bonding. “Anyway, let’s give ‘em back. I don’t know if this place even bothers returning lost items. They sure didn’t that time I forgot some of my magician cards over vacation.” He scooped a few blocks into one arm, and a ragdoll, and the toy train into his other arm, and—

“Say, what’s this doing here?” Yona said, as she picked up a colorless crayon from the trail of items. It was clear, almost entirely see-through apart from the yellowed paper wrapped around its middle, which yielded no information, mentioned no color. When held up to the light, it possessed an iridescent sheen. Her mouth curled into a smirk.

“What is it?”

“I recognize this trick. That time I cheated grading papers during my trial. I guess you didn’t have those, right? Because Eastern Manyas don’t wear hats. Anyway—this isn’t some ordinary crayon, it’s been imbued with a very special kind of magic. Under the Playful domain.”

“Come again?” Rory said, no more enlightened.

Yona sighed. “Magic falls under six different domains: Scenic, Healing, Artistic, Harmonic, Playful, and Introspective. Were you asleep during ALL of Mr. Kivel’s lessons? The point is, that kid’s gotta have some advanced magical senses to make something like this. Here, watch.”

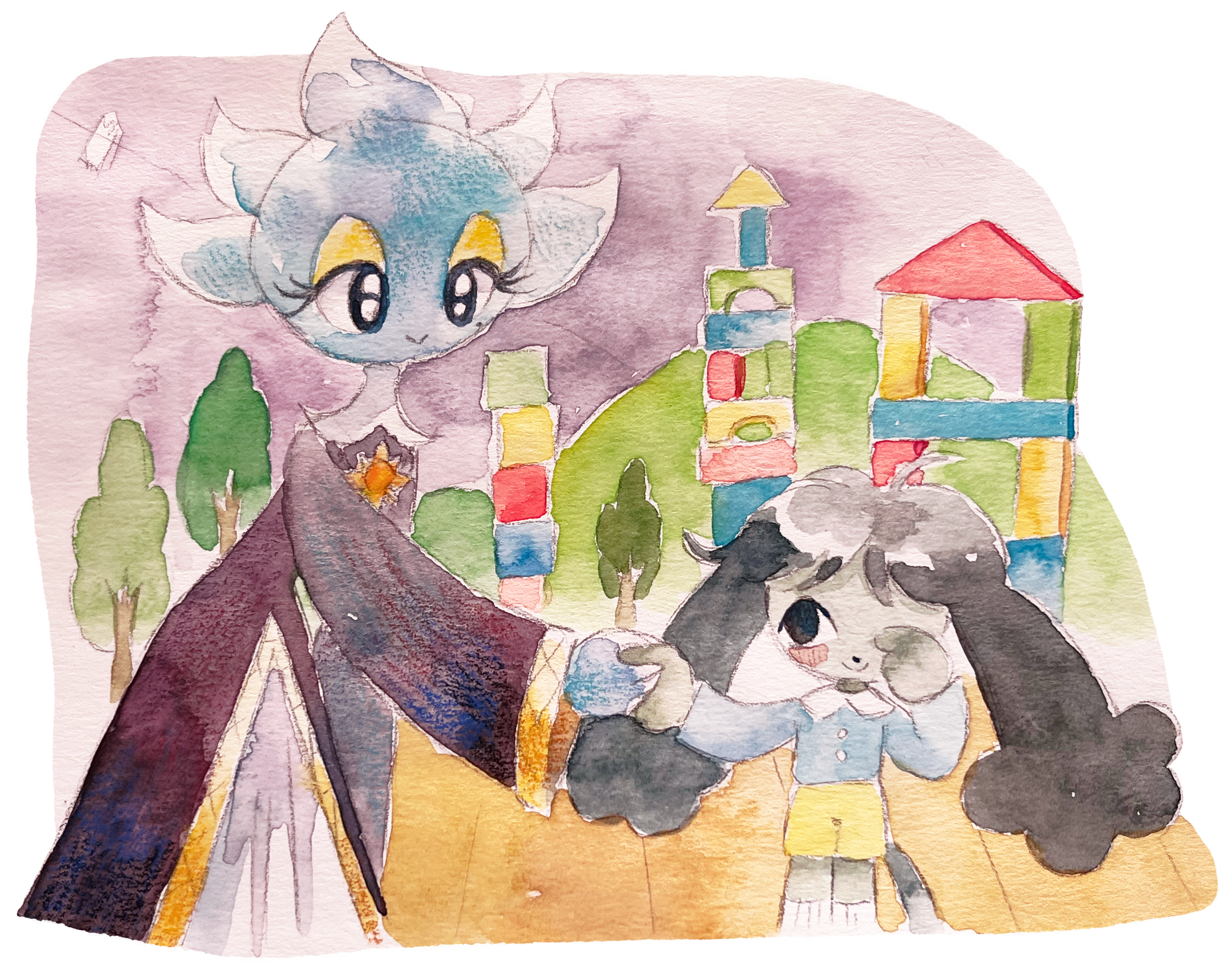

Yona waved the crayon in the air, drawing invisible loops and curls, gripping it tightly; she then squeezed it out from her paw and it began tracing circles above them on its own, levitating, just like the magic pen from her youth. Awestruck as they watched, the crayon proceeded to draw an opening into another scene, another place. Peering into the portal, Yona and Rory nearly lost their noses as a toy firetruck came careening past them. It was the contents of a great big toy box spilled into a miniature utopia of building block roads and construction paper skies, and as their eyes darted to and fro at the paracosm before them, the child who had blazed past them in the hallway was seen sprinting towards a cuckoo clock tower. Like Alice in pursuit of the White Rabbit, they knew they should follow.

Promptly, Rory tripped over a large jack which elicited laughter from some unseeable entity above, as thunderclaps of merriment rolled throughout the town. Just where was this place? Glass Grotto had been a tangible, geographical location anyone could point to on a map of Odoken, but was this truly only an imaginary world they’d been whisked to? Or could Yona and Rory have still been sound asleep in their rumpled hotel beds, zone traveling together to some place lightyears away?

Where the truth lie did not immediately concern them. What did concern them was the way wooden cars sped, not on paved roads, but wherever they pleased; how painted block buildings stacked themselves only to be knocked down seconds later by an invisible force; and the motionless giant paper dolls and wooden figures that were the closest approximations to other living beings they could find, silent, perhaps silenced. It was an entire pocket dimension of playthings, happy things, yet so removed from their intended context that they seemed menacing, perhaps even oppressive.

The only place the wooden cars didn’t drive were the train tracks weaved throughout the town. Yona and Rory nimbly walked along them, keeping their eyes and ears alert in case the train should come at a moment’s notice, seeing as how nothing seemed to follow any logical sequence in this world.

“D’you think you would’ve liked this place as a kid?” Rory said.

“Uh, I doubt it. The whole thing is definitely under someone’s control. I would’ve liked it if I could be the one pulling the strings, maybe, but as it stands…don’t you get a creepy feeling being here?” Yona said, a shudder rippling down her spine. Rory nodded.

“The kid’s nowhere in sight, either…and my feet are killing me…”

Yona suppressed a smile. “Why do you wear sandals everywhere, anyway? Couldn’t you have brought sturdier shoes?”

“You basically wear slippers everywhere and I don’t see how that’s much different. They don’t really sell shoes that aren’t sandals in East Majonia. Maybe we shoulda gone shopping before this trip. I miss doin’ my handicrafts, too.”

Yona faced forward with resolve. “When we get back there’ll be time for all the handicrafts in the world, believe me. And who knows, maybe I’ll even buy one this time.”

“You always say that…” Rory mumbled.

* * *

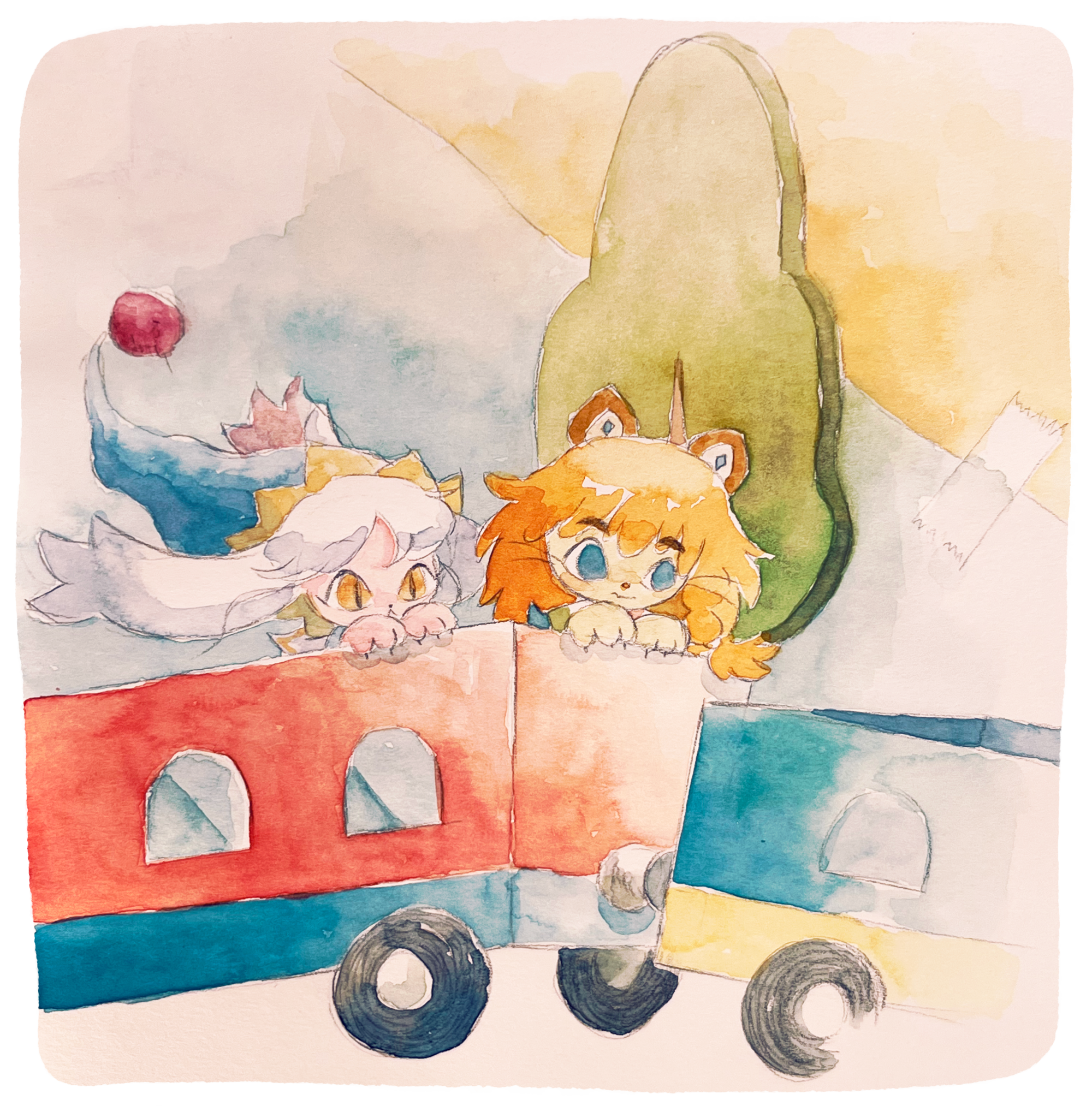

When Yona and Rory reached the toy train station, the cuckoo clock tower at last seemed near at hand, finally visible past the log houses and cutout trees. It had been chiming with each hour passed—a stark reminder of how long they’d spent on foot—but now they could see trains in the station, all plastic and smooth and gleaming, and the pair reached an agreement that fighting against the logic of the place may not have been in their best interests. A little chaos is good in small doses, after all. They hopped into a train cart, which felt much like being in their mother’s shopping cart as a child, and dug their claws into the painted plastic in lieu of seatbelts.

“How fast you think this thing’s gonna go?” Yona said, bearing a mischievous grin.

Rory hadn’t even considered it, and now his whiskers were anxiously twisting into knots again. “Hopefully nothing like the wooden cars. Y’know, I don’t do much good with vehicles—always get real queasy, even when they don’t go too fast…”

“But didn’t your parents—er, your family assistant—fly you to school every day when we were kids? How’d you manage that five days a week?”

“Oh, I didn’t. It was awful. Sometimes as soon as he dropped me off I’d run for the bathroom, ‘cause—“

Suddenly the train let out a puff of steam, sounding its whistle, and they began to roll out of the station. What started as a steady departure soon had the pair rocketing across the track, in a blinding mad dash of pure speed that better resembled a roller coaster than a train ride. Even keeping their eyes open to watch their surroundings stung against the oncoming blasts of wind. The world around them was little more than impressionist splatters of color being flung past them. When the train finally reached its next stop, the sudden sharp halt was enough to give them whiplash.

Their claws finally relinquishing the death grip they’d held throughout the duration of the ride, the pair clumsily scrambled out of the train cart and sunk to the ground, relishing in the dizziating sparks that flashed behind their eyelids before quite regaining consciousness. It was then that Yona noticed she was sinking into something of a dreamlike state—perhaps it was some impromptu zone traveling?—but, No, she thought; this was more akin to a trance. She could not control this.

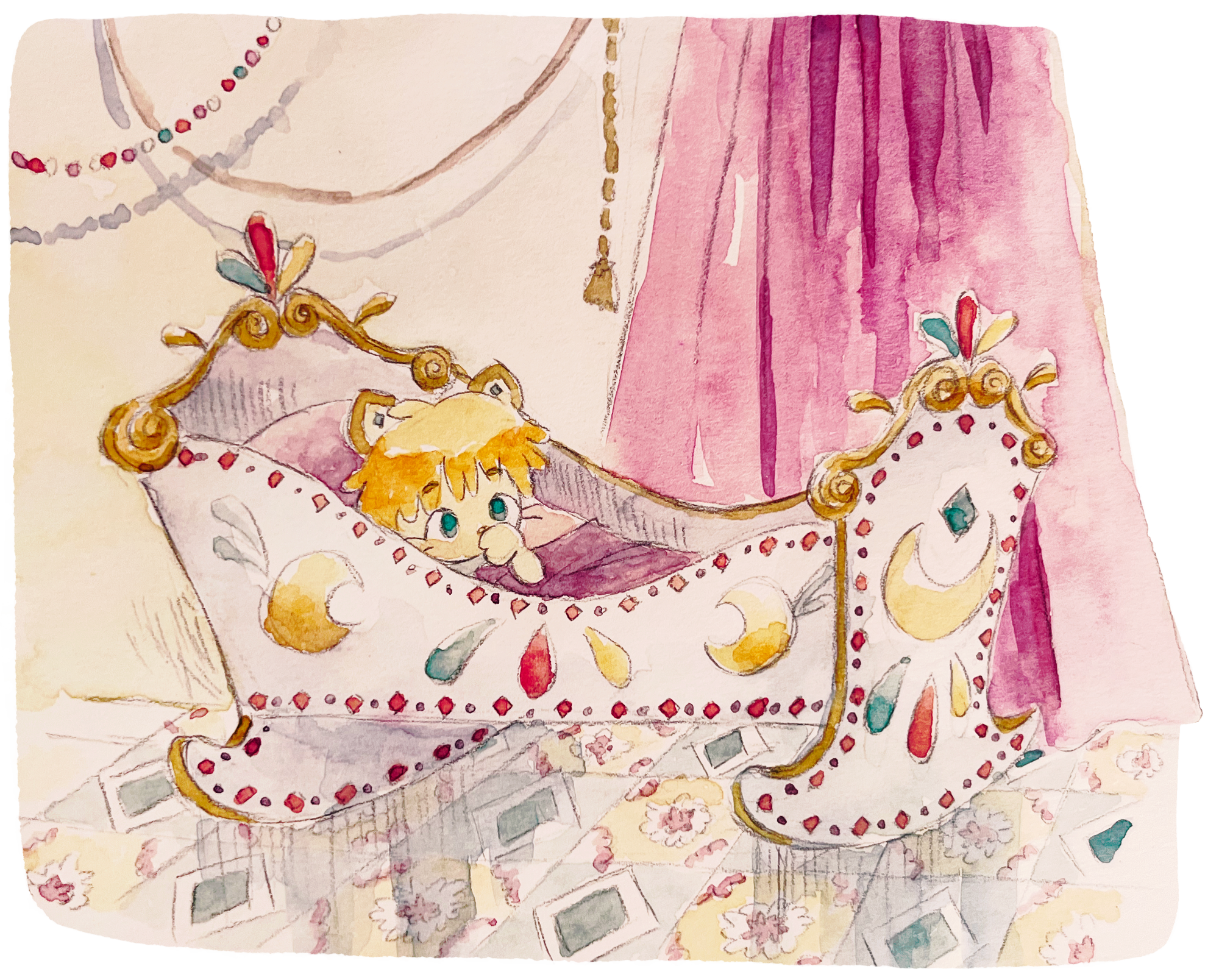

Rory remembered a cradle, all adorned with gold trim and rubies, and a cashmere blanket. He remembered the clamor of a few dozen people in the vicinity—saying what, however, he could never make out. He remembered the sunken features and wooly beard of a very old Manya man as he lifted him out of said cradle, proudly proclaiming him the son of the ambassadors of East Majonia, to a round of applause from the sea of strangers. But he did not see the faces of his parents, whom seemed to be somewhere in the distance, about as far as his newly-opened eyes could see—drinking and talking with someone who looked very important. The last thing he remembered was letting out a cry.

Yona remembered ice. She had been cold, cold for a whole lifetime, but now her eyes were open. The ice had melted. She swam all across the Novas Ocean, though she had just been born, and hadn’t spoken a word to anyone. The harrowing clouded dark once the sun had gone and the moons were the only things above the sea was her sole motivation to keep swimming. And she did reach land, eventually, though the people upon it, as much as they may have resembled her, weren’t much kinder than the cold ocean. Life was her own to make of it as she willed—but why?

To their surprise, the foreboding chime of the cuckoo clock tower resonated throughout the town once again, and the traveling adventurers were awake and present once more, although they hadn’t regained the emotional composure needed to get to their feet. They had been elsewhere, places that no longer existed, and confronted buried thoughts and moments they’d hoped wouldn’t return to the surface; yet there they were, puppeteered back to life by some unseen force. Yona need only take one look at Rory to know he’d just weathered the same storm.

“Who—what—“ she began, at a loss.

“Why…did they make me think about that?” Rory said, tears welling in his eyes. “I didn’t want to remember what it was like being so…”

“Alone?”

Rory nodded, struggling to get the words out.

“Yeah. I didn’t want to remember it, either. Something’s playing tricks on us here, and I suspect that that kid knows something.” She brushed away some unexpected tears of her own with her sleeve, discomforted by the knowledge that even she was susceptible to whatever strange emotional manipulation this world had in store for those unlucky enough to stumble into it.

“Was it the same memory you used to tell me about—about the sea?” Rory asked, unsettled.

“It was. I feel like they made me swim all those miles again, just now.” Yona laughed in spite of herself. It really was a very hazy and dreary memory, one she could never make sense of, but it was the earliest recollection of life she had.

However, better things were ahead: “Look, the cuckoo clock tower’s finally close. Let’s hurry and get out of this place, okay?” Yona said, extending a paw to her friend. Gingerly, Rory took the paw into his own and nodded. The two began walking, then sprinting, towards the vibrant yet foreboding monolith that looked as if it desired nothing more than to carelessly topple over the two, leaving them never to be found. Then came into their sights the Manya child from before, scaling the tower up to the clock’s face, looking dreadfully mischievous as though he was hiding some terrible secret he was proud of.

“Quick, we have to follow him!” Yona hollered. “I don’t know what he’s doing, but he definitely knows we’re after him.” The pair began scaling the block building in hot pursuit. The Manya child reflexively looked over his shoulder once or twice, muttering something under his breath that seemed rather pleased.

Atop the cuckoo clock tower one could see the whole layout of the town, with its labyrinthine structure making all but the one path they took incapable of reaching the tower, and a slight tear in the construction paper sky above that emitted the feeblest ray of real light. One could also see the bright block buildings knocking themselves over and rebuilding themselves again sporadically, and the pair suddenly came to the nauseating realization that nothing was preventing this unseen force from doing the same to the very structure they stood upon. Rory gulped.

Yona approached the Manya child, who stood turned away from them, his gaze fixed on no point in particular. She placed a confrontational paw on his shoulder and said, “Hey, you! Just what do you think you’re doing, sending us on some wild goose chase like this? What even is this world, anyway? It’s vicious and nasty and no one knows how to drive, and the people aren’t real, and the infrastructure is a mess, and are you even listening to me?”

Suddenly, in the crumpled creases of the sky, words were formed by some invisible, gargantuan blue crayon that read: “This is my world. You weren’t supposed to find it.”

Rory scratched his head. “But it seemed like you were leading us to it.”

It scrubbed the previous words and wrote: “I was not. I hate adults.”

Yona, like clockwork, nearly retorted “But we aren’t adults,” before remembering she had twenty-two years to her name, and Rory twenty-one. They certainly didn’t feel like adults, not in the way that Pamela and Lonissa and other such folks were.

“We’re sorry, I guess. Why do you hate adults?” Yona asked.

Once more it wrote: “I hate the world of adults. You took away all my fun.”

“Hey, we didn’t do that,” Rory chimed in. “Maybe other adults did that, but we sure didn’t. What is it you want?”

“To play,” the crayon wrote.

“Haven’t you played enough? You created an entire world where all you do is play. And you play mean. Rory and I could’ve been killed by the way you drive cars alone,” Yona said. “I’m not interested in playing with some stubborn baby who only wants it his way.”

Suddenly, a large jack flew through the air and knocked into Yona with considerable force. “Ow! That’s exactly what I mean, see?!” she fumed. The sky once more roared with a laughter that reverberated throughout the town.

“Leave her alone!” Rory hissed. “You’ve got Glick’s doll, don’t you? We’ll negotiate. Anything you want. But don’t throw things anymore!”

Yona, pleasantly surprised by Rory’s bravado, then gained the courage herself to say: “If it’s a challenge you want, bring it on!”

The crayon then changed hues to a warning red, and wrote: “WHY CAN’T YOU UNDERSTAND?” before the foundations of the cuckoo clock tower began to crumble beneath them. The beams of the building split apart and fell in all directions as the group violently tumbled to the floor below.

Amidst the sad wreckage of the cuckoo clock tower the three Manyas lie, coughing and struggling to pull themselves out of the ruins. Why would that kid have done this, Yona wondered. He appeared quite worse for wear himself. However, before their very eyes any trace of injury upon their bodies vanished in a matter of seconds, as if they had imagined it. Rory, whom had been twisted into a pretzel upon landing, managed to stand on both legs and feel no pain minutes after their dangerous descent. Not wanting to test the laws of this unpredictable universe, Yona cautiously stumbled to where the Manya child sat, still turned away, and asked him: “Are you hurt anywhere?”

They looked upward toward the sky in anticipation of the crayon’s response: “No. Just leave me alone.”

She opened her mouth to say something, then promptly closed it. Perhaps it was all the talking that had gotten them into this mess, she thought. Sitting atop a piece of rubble, she squeezed her eyes shut and considered their current predicament. She thought about the wooden cars and plastic trains, about the parchment paper sky and that small sliver of light that poured out of its tear. She thought about the metal jacks that could be hurtled from nowhere. She thought about nowhere…and everything that can come from it.

Suddenly she imagined a shiny, red rubber ball. It was much like the one they used to bounce around the orphanage, when the children were all huddled up in their beds pretending to be asleep. Oh, the amusement that red rubber ball had brought them! She would bounce it in her paws, then throw it against the wall; it would bounce off so marvelously into the next bed, where another child would fling it against the wall behind him, then it would make its way to the next row of beds. And it was so quiet, neither of the headmasters ever found their game. That shiny, red rubber ball…where were you now? Why, you’re right here, right before my eyes!

It was as clear as she had pictured it when she opened her eyes to find the red rubber ball manifested into reality. So this world could be controlled by an outside force! Startled, the Manya child backed away with a start, saying not with writing but with his mouth, “What are you doing? What is this?”

“If you think this world is just for you, two can play at that game,” she grinned, some of that old mischief rising to the surface again. The red rubber ball, lifesized, bounced boisterously through the town, ricocheting off block buildings and toppling them, just like the invisible force had continually done.

“Stop it! I’m begging you, stop it!” the child fumed. “Only I get to break everything!”

“And why is that?” Rory asked.

“Because this is all I have. This is the only thing I get to control. Please stop,” he pleaded, as tears filled his eyes. As soon as he had made his request, the ball shrank down and morphed into a paper flower standing upright on the floor. Yona opened her eyes.

“I’m not trying to upset you, kid. We just wanted to talk, but you weren’t til now. How come?”

“I already told you,” he sniffled. “I hate adults.”

“But why? Everyone becomes one someday. It’s not that different from being a kid,” Yona said, placatingly.

“Yes, it is! People become awful when they grow up…and you can’t do the things you love anymore.” He brushed his tears away and changed his face to a scowl. “I don’t want to live in a world like that. I want to live in a world that can be whatever I want.”

“But when you grow up, you have the power to make that kind of world,” Yona said. “Sure, there’s parts of being a grown-up I don’t like…but I didn’t change that much.”

Rory added, “She’s even still got all those magician trading cards she had when we were kids.”

The Manya child sniffled, then looked at Yona knowingly: “You have those too?”

“Oh, of course I do! I wouldn’t be me without ‘em!” she laughed. “Do they still make them? Which one’s your favorite?”

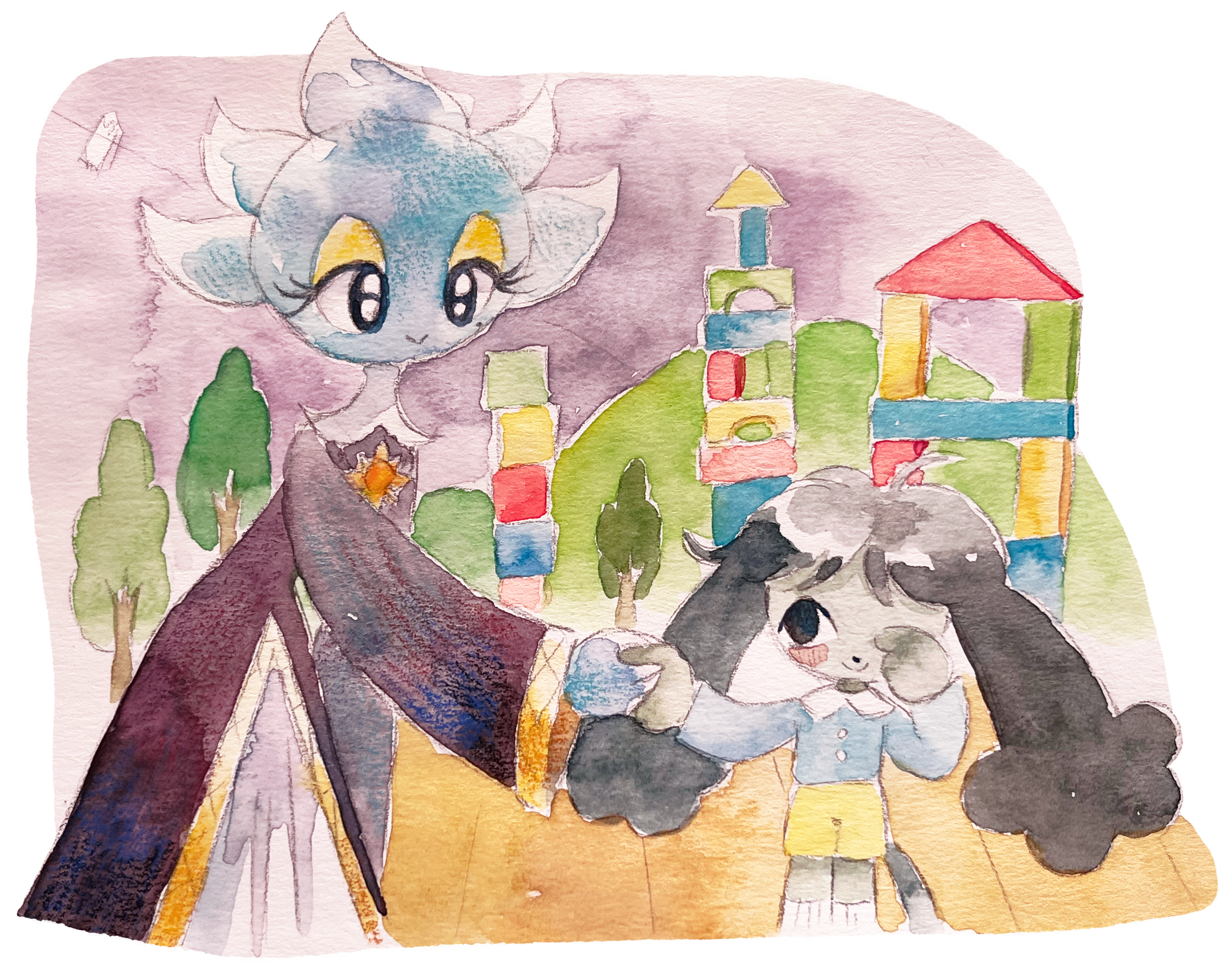

“I think Duskell’s pretty cool,” he said, considerably calmer than he was moments ago. Then from thin air emerged a paper doll of Duskell, smiling and waving to the Manya child, speaking in a voice more similar to Yona’s: “Why, hello there little boy! Who might you be?”

“I’m Lavi,” he said, cheeks rosy with a joy Yona nor Rory could ever have imagined him with. “It’s nice to meet you, Duskell. I’ve only seen you on TV.”

“Why, what a lovely lad you are! You know, I was just thinking that I’ve been on so many travels as of late, I’ve gotten rather bored of the whole thing. Won’t you play with me? Perhaps we could have a delightful tea party, or imagine ourselves as sailors at sea?”

“Sure, that sounds like fun,” Lavi smiled. He took her flimsy hand in his, somehow warm despite the lack of a pulse inside of it, and the two began setting out the blanket and teacups while chattering happily about how they were to be king and queen of some dazzling enchanted forest. But before Yona or Rory could say anything, the world filled with light from above.

When their eyes were open, what they saw was the wood panel of the hotel floor and the scattered toys—no longer looming over them, but little and handheld, the size that toys are meant to be—as well as another one of Glick’s wind-up dolls, sat patiently before them. They blinked softly.

“How’d you know you could do that? Imagining things to make them real,” Rory said after coming to. “We could’ve been stuck in there forever if it weren’t for your inner kid.”

“I just figured, it was the kid’s imagination that made that world possible, so the only thing that could disrupt it was someone else’s imagination, right? Anything I thought up, it could be just as powerful as whatever he came up with—so long as it was fun. I think deep down, all he wanted was a playmate.”

For no particular reason she began picking the toys up, possibly to return them to Lavi in the event that he was still running free in the real world. As she grabbed the train cart she and Rory had rode in hours before, a grown Manya man approached them, heavy in his footsteps, yet gentle in his demeanor.

“Oh, did someone leave those behind?” he asked. Perhaps he was hotel staff, she thought, though there was something familiar in his features. “Let me take those off your paws—what a mess! You know, I used to have things just like this when I was young,” he said with a thoughtful look in his eyes.

Rory glanced at Yona and once more knew that they shared the same thoughts. The pair smiled at the gentleman, grabbed Glick’s doll, then took their leave.

|